The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy

The Quiet Collapse that Paved the Way for Today’s Bureaucratic Nightmare

I was sipping tea, scrolling through my phone, when I stumbled upon a fascinating series of articles published in American Tribune, a Substack whose work I greatly admire. One article, in particular, addressed several major political catastrophes that shaped the 20th century. Intrigued, I read through the list and felt a strong pull toward David Cannadine’s The Decline and Fall of the British Aristocracy.

I’m not sure why, but something about that stretch of time from the late 1800s to the mid-1900s piqued my interest. On one level, we hear so much about the World Wars and the ensuing liberal world order. And yet, that critical chunk of history has all but vanished from public discourse. It seems to me that something profoundly significant lurks amid those overlooked decades.

The book poses a seemingly straightforward inquiry: How could a class that once owned half the globe’s map fade to near-obscurity in just a few decades?

Cannadine’s own summary sets the stage:

“At the outset of the 1870s, the British aristocracy could rightly consider themselves the most fortunate people on earth: they held the lion's share of land, wealth, and power in the world’s greatest empire. By the end of the 1930s they had lost not only a generation of sons in the First World War, but also much of their prosperity, prestige, and political significance.”

And this raises a somewhat broader point. Beyond the mere historical drama, how did we wind up stuck in this squalid, bureaucratic nightmare we now call ‘the Yookay’? I suspect the dissolution of this high-status class provides us with a critical clue.

Given all that, I’ve gathered five standout passages from Cannadine’s book that illustrate the downfall of Britain’s aristocracy—what triggered it, how it progressed, and the far-reaching consequences. As we go, I’ll also highlight the concept of systemic agency, a key catalyst in this story, and something that will become more important in future articles. Let’s get started.

1. Loss of Power & Direction:

For one thing, it’s striking how disoriented everyone seemed by the turn of the 19th century. The aristocrats—people like Wilfrid Blunt and Oswald Mosley—had long seen themselves as natural successors in a natural tradition of legacy and stewardship. Tragically however, the political and economic landscape was beginning to destabilise beneath them.

As Cannadine chillingly observes in one passage:

“They no longer knew where they were, who they were, what they were doing, or where they were going... Disoriented and disenchanted, these renegade patricians were boxing the political compass, unable to see their way clearly in a world where their aristocratic presuppositions seemed increasingly irrelevant and anachronistic.”

That term—‘boxing the political compass’—evokes an image of an upper class flailing at ghosts. On the one hand, they still possessed wealth and estates. Still, their ability to influence the broader landscape around them—their systemic agency, in other words—was fading fast.

“Open your eyes. The world doesn't need revolution. It suffers a little too much from that already. I don’t care if your intentions were noble—you cannot expect to betray your masters and live long afterwards.”

—Gav Thorpe | The Lion

2. Economic Displacement & Policy Failure:

Make no mistake, the ancestral nobility tried to hold on to their estates like castaways clinging to lifeboats during a violent storm—like those offering up a final prayer after faith had faded.

But the world around them wasn’t slowing down: new land laws popped up, taxes went through the roof, and everyone seemed to care more about what was happening in the cities than the countryside. As Cannadine puts it:

“The gentry and grandees were gradually becoming the anxious but frustrated defenders of their own peripheral vested interests… Their efforts to protect agriculture, to thwart the Liberal land campaign, and to revive the rural community under genteel leadership were singularly unsuccessful.”

Put bluntly, no amount of clandestine deals or nostalgia-soaked oratory could reverse the surge of modern progress. Every attempt they made—whether to ‘preserve,’ ‘resist,’ or ‘reawaken’—ended the same way: in deflated expectations.

For all their pedigree and pomp, the aristocrats didn’t own the media and couldn’t sway the opinions of those in urban centres. Their impassioned last stand might as well have been a child’s sandcastle facing the inevitable rush of the sea.

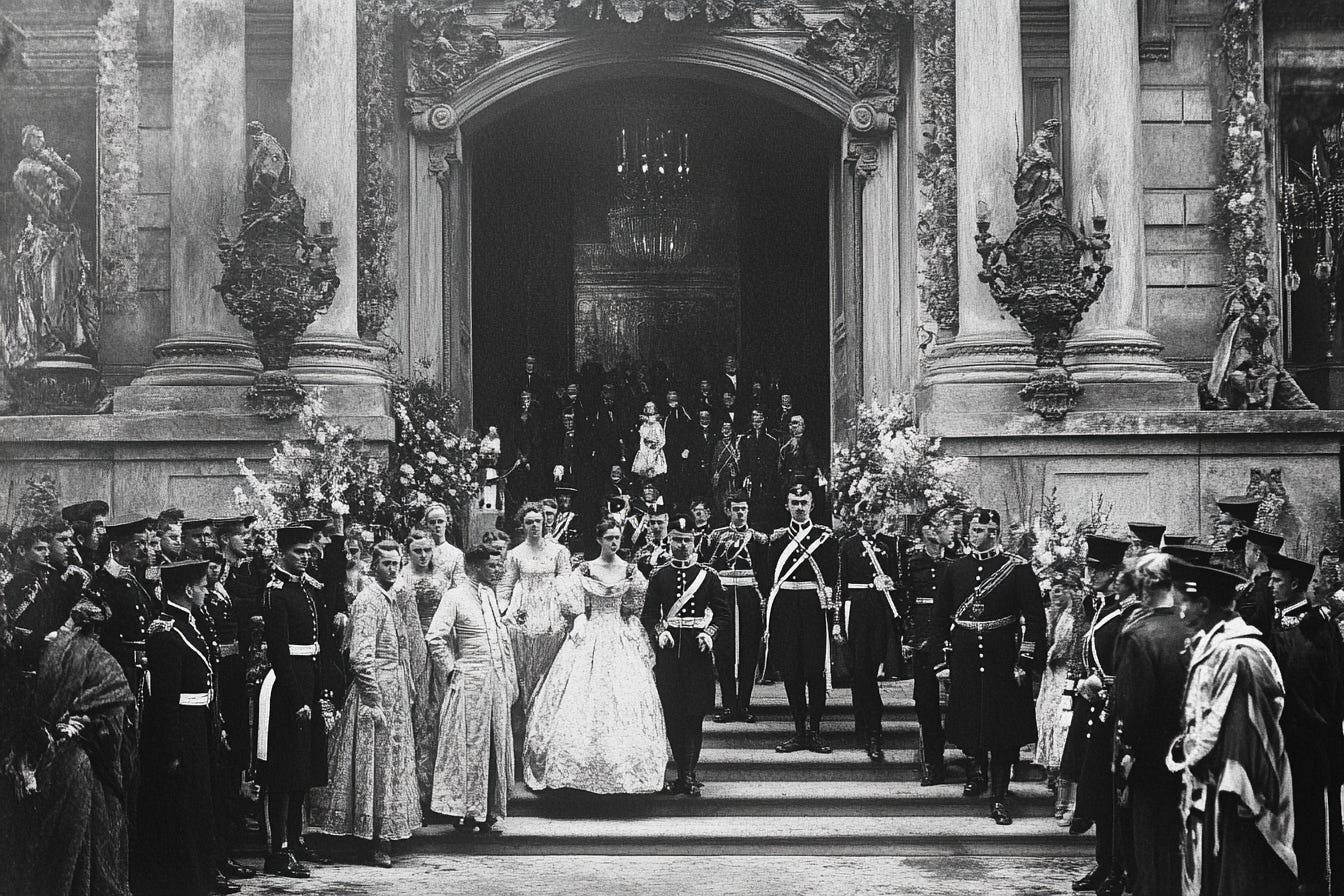

3. The Devastation of the First World War:

If the aristocracy’s fate was all but sealed in late Victorian Britain, the First World War delivered the final blow. Cannadine’s words bring home the bleak reality:

“Although they had fought like knights of old, they had been slaughtered like animals, and had fallen like flies... Their collective self-confidence and their serene faith in their ultimate invulnerability were irretrievably damaged.”

Imagine those vast countryside mansions with no heir left to inherit. Although every stratum of society suffered in the war, Cannadine emphasises the exceptional blow dealt to the aristocracy, whose members frequently led from the front and, in many instances, perished in muddy trenches.

“He is the best of us—in him all things are found in balance. And yet, every facet is raised to excellence. For which of us could match his grace, his compassion, or his understanding of the human condition? And yet our brother is unbalanced, profoundly so: He represents the very best and the very worst of what it is to be one of us. He is the noblest of us. But also the most fearful. A glorious creature, enslaved by insecurities.”

—Aaron Dembski-Bowden | Betrayer

And it’s also true, I think, that those who did manage to survive returned deeply changed, recognising, as Mosley argued, that the conflict was waged for cosmopolitan interests rather than genuine nationhood, ultimately serving international finance rather than patriotic ideals.

4. Emotional & Cultural Reactions:

After 1918, the aristocrats who made it out of the trenches were left wrestling with guilt and despair, and in some circles, they dove headfirst into wild excess. Cannadine sums it up like this:

“Inevitably most surviving patricians, both young and old, contemplated the future with gloom and despondency that sometimes bordered on alarm... Some surviving aristocrats felt a genuine sense of guilt that they had not shared the ultimate fate of their comrades and companions. Others... abandoned themselves to irresponsible self-indulgence.”

These men embodied a kind of moral whiplash: some felt huge waves of guilt, while others ran down their fortunes chasing thrill after thrill. Both reactions, however, indicate a shared sense of cultural rupture.

In short, when the war upended their world, these lords and heirs found themselves unmoored. After all, guilt and abandon, while seemingly contradictory, both arise in the absence of what once felt stable and enduring.

5. A Fragmented & Contradictory Legacy:

As their power slipped and their fortunes shrank, the British aristocracy branched out in different directions. Some retreated to remote estates, while others rebranded themselves as key players in a more superficial cultural arena.

“By definition, when a class is in the process of decline and fragmentation, not everyone behaves and responds in the same way... while some aristocrats vainly and violently lamented their loss of power and prestige, there were others who were enjoying a period of renewed and unprecedented social celebrity... they had become the great ornamentals.”

That final label—the great ornamentals—felt both fitting and painful. These people, once decisive shapers of the nation, had become little more than ornamental fixtures in Britain’s ever-evolving cultural display.

Although they tried to maintain the prestige of their name, the financial muscle and influential clout they once wielded had disintegrated completely. Even those who ventured into new businesses became little more than tokens of a bygone splendour—pale shadows of their former selves.

6. Wrapping Up:

They had once administered entire counties with a mere flick of the wrist, but over time Britain's aristocracy disintegrated bit by bit, fading into near-obscurity. In Cannadine’s analysis, they lost their public significance not through sudden revolt; rather, they drifted into modernity unprepared, without a compass to guide them.

His work doesn’t merely address bureaucracy or economic shifts; it lays bare how deeply fragile those noble titles really were. Overcome by a cocktail of anxiety and regret, these aristocrats witnessed the collapse of their inherited authority. Cannadine describes them as ‘boxing at shadows,’ paving the way for Britain’s gradual transformation into what many now mockingly term the ‘Yookay.’

The truth is, like it or not, that old ruling class is a thing of the past, and in its place are huge institutions, in thrall to complex institutional forces beyond all human understanding, which every day become more convoluted, unpredictable and self-serving. Indeed, the permanent Civil Service, the courts, and their associates now command a large part of the economy, and uses these resources to grow themselves still further.

More disconcertingly still, we remain passive observers, uncertain whether a dismantling process is even feasible. It’s the final exasperating irony: the once-celebrated aristocracy proved unable to maintain its hold on society, while today’s managerial class don't seem to know how to do anything but metastasize.

The first world war basically ended any mandate aristocracy and monarchy had. I should put together a substack article about this, because I think most people overlook that the World Wars are very significantly a matter of deciding how the world is to be governed - it is increasingly clear that the days of royalty/monarchy/aristocracy are tottering as we open the 20th century, but how and when that will change and what will or won't replace it is still very much up for grabs at that point - though of course the spectre of Communism was haunting Europe, and democracy had turned France into a Republic in a fashion that rather alarmed everyone else (eg, with guillotines and Napoleon).

I think the big picture is pretty simple, although the details are complicated. When one gives up the printing of the nation's money supply and the media to foreign interests of a different religious persuasion, over time the bloodsucking will drain that nation of all of it's strength and vigor. And this happened because the aristocratic stock of that nation adopted the God of those people and handed it over on a silver platter.